At the Intersection of Asian American and Queer Studies: A Q&A with Amy Sueyoshi

Amy Sueyoshi, Dean of the College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University, is a leading scholar and curator in queer Asian American history. In advance of their October 25 PHI talk, Cornell history PhD candidate Emily Donald conducted this Q&A with Dean Sueyoshi about their research and their path into public history.

Your scholarly and curatorial work sits at the intersection of Asian American and queer studies. Can you talk about how you see the connections between these areas of study? I am curious if working at the intersection of academic scholarship and curatorship has also helped you to access and illuminate the connections—or sometimes disconnections—between Asian American and queer studies.

When I first began my graduate student career researching at the intersection of Asian American and queer studies, the easiest and most obvious answer was that both fields needed to be more invested in taking the intersection seriously. I think it was in large part because I saw so few publications and felt professionally so completely ignored and unvalued, particularly in history. For sure the two fields seemed largely disconnected. Part of my work thus has been to illuminate the interconnectedness and how that interconnectedness can be radically transformative for the queer API community for whom I write. I realize that my scholarly work is different from my curatorial work, but at the same time I see them as in relationship with each other, perhaps like a see-saw. My scholarly research is crucial in how I curate, and my curatorial work has enabled me to be a better scholar. While historical research is often solitary work, curation for public projects requires collaboration with other historians, community partners, and sources with which you wouldn’t normally engage. It gives you a larger lens from which to think about your research and that is in turn critical for framing academic scholarship.

You are a founding co-curator of the GLBT History Museum in San Francisco (est. 2008), the first queer history museum in the United States. Can you speak to the significance of the museum and how its place in the local Castro and broader US queer community has changed over the years?

I was so honored to be a part of this project and it was a whirlwind when the museum first opened. We received so much national and international attention, and for the first five years I was extremely busy mounting exhibits, meeting with the press, and hosting curator tours. I was so busy that I didn’t have a moment to enjoy what was really going on, plus I felt shy about pronouncing the uniqueness of our museum, particularly in San Francisco, and what that has enabled us to do. After countless conversations with visitors though, as well as a talk by one of the other co-curators Gerard Koskovich declaring our obligation to set a model of what queer life could be, I’ve come to more proudly embrace being able to be active in San Francisco’s queer community as more than just an activity for myself, but rather as a larger responsibility in the creation of a global queer community and consciousness. Shortly after the museum opened a number of other galleries and exhibit spaces across the country began to declare that they in fact had a queer history museum as well. I appreciated this competitive spirit that has spurred a number of other institutions and activists to bulk up their work exhibiting queer history. What this means is that now in any number of cities such as Chicago, New York, and Los Angeles, you will likely be able to visit an exhibit if not museum on queer history.

One of your public-facing projects was the section on Asian Pacific American queer history for the National Park Service’s LGBTQ Heritage Theme Study (2016). I actually assigned your chapter for my first-year writing seminar this semester as an example of a public queer history project. My students were enamored by the many compelling stories and individuals you write about, and they were curious as to what this piece was used for, how it was distributed, and how it was received by readers. Could you speak to any of those questions?

The National Parks Service first approached me to do the essay on API queers when they were given the green light to the LGBTQ Theme Study. It was a pretty momentous green light, the first ever queer theme study that the NPS embarked upon to consider more queer landmarks. The collection of essays therefore is expansive and specific with addresses and specific sites. The editor Megan Springate really deserves a standing ovation for their efforts. The article along with the other essays were simply posted on the NPS Theme Study website. We found out later that the collection won an award from the Vernacular Architecture Forum. I presume the theme study has been used for consideration of more landmarks, but I do not know. I do know that my essay specifically has been used in a number of educational venues such as the classroom and diversity trainings at corporate and governmental organizations. A number of my colleagues in Asian American Studies have been so appreciative of the article. I think it serves like a meat and potatoes reading in any week or course on queers or Asian Americans. It was even translated into Japanese for a queer studies anthology in Japan when the essay first came out. More recently, since the Thai grandpa Vicha Ratanapakdee was killed and the STOP API Hate movement gained national attention, people who are not API are taking an interest in the article. This has been really surprising to me. It’s like “What, you actually care about queer Asian American history?!” In September, even Estee Lauder the cosmetic company approached me.

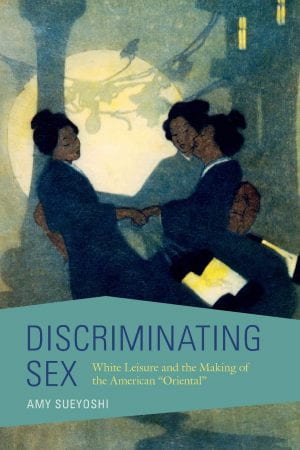

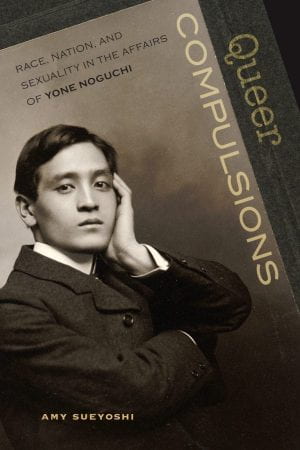

In addition to your curatorial work, you have published two academic monographs, Discriminating Sex: White Leisure and the Making of the American “Oriental” (2018) about how middle-class white desires for sexual and gender fulfillment gave way to racialized caricatures of Chinese and Japanese immigrants from the late nineteenth century, and Queer Compulsions: Race, Nation, and Sexuality in the Intimate Life of Yone Noguchi (2012) about how queer intimacies can sometimes reflect rather than revolt from existing social inequalities, as individuals negotiate affections across cultural, linguistic, and moral divides. What drives you to read at the intersection of racialization and sexuality in Asian American and US history?

It’s because I’m queer and Asian and my primary audience will always be my peeps in the community! I have great love for both queers and Asian Americans, and I take pride in saying I am an Asian American queer. I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area feeling deep shame for being Asian, not shame about our incredible history, but more like shame for being ugly, for being inarticulate, for being less athletic, less cool compared to white folks. I remember the kids at school used to tell me I was “eating shit” whenever I pulled out my bento or onigiri because of the layer of seaweed on top, and now they sell it on these food trucks that are so over-priced I can’t bring myself to buy it. Needless to say a lot has changed, and growing up in an Asian American community

It’s because I’m queer and Asian and my primary audience will always be my peeps in the community! I have great love for both queers and Asian Americans, and I take pride in saying I am an Asian American queer. I grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area feeling deep shame for being Asian, not shame about our incredible history, but more like shame for being ugly, for being inarticulate, for being less athletic, less cool compared to white folks. I remember the kids at school used to tell me I was “eating shit” whenever I pulled out my bento or onigiri because of the layer of seaweed on top, and now they sell it on these food trucks that are so over-priced I can’t bring myself to buy it. Needless to say a lot has changed, and growing up in an Asian American community  allowed me to later recognize its strength and beauty. Since coming out, API queers have given me so much, even as they have so little to share. Many of us are rejected from our families, face daily abuse on the street, and rendered invisible by society at large. I feel their pain and also their love at every single potluck or dim sum gathering. I am inspired by their fortitude and conviction to live their best lives – the dyke firefighter who has to supervise a bunch of dudes, the butch plumber who works at the women’s prison teaching other women the trade, and non-binary programmer who feels disconnected from the other geeks on their team. All of them still call their elderly moms, take them out to lunch, and take them on walks even as the immigrant moms not-so-quietly criticize their clothing and their “failures.” It’s for them, and for myself that I do the research that I do and I am so grateful that I am able to have a job that affirms my identity and pays the bills. I realize that in the academy we may often be discouraged from studying “ourselves,” but I tell my graduate students you have to feel personally connected and passionate about your work to take you through the darkest days of graduate school.

allowed me to later recognize its strength and beauty. Since coming out, API queers have given me so much, even as they have so little to share. Many of us are rejected from our families, face daily abuse on the street, and rendered invisible by society at large. I feel their pain and also their love at every single potluck or dim sum gathering. I am inspired by their fortitude and conviction to live their best lives – the dyke firefighter who has to supervise a bunch of dudes, the butch plumber who works at the women’s prison teaching other women the trade, and non-binary programmer who feels disconnected from the other geeks on their team. All of them still call their elderly moms, take them out to lunch, and take them on walks even as the immigrant moms not-so-quietly criticize their clothing and their “failures.” It’s for them, and for myself that I do the research that I do and I am so grateful that I am able to have a job that affirms my identity and pays the bills. I realize that in the academy we may often be discouraged from studying “ourselves,” but I tell my graduate students you have to feel personally connected and passionate about your work to take you through the darkest days of graduate school.

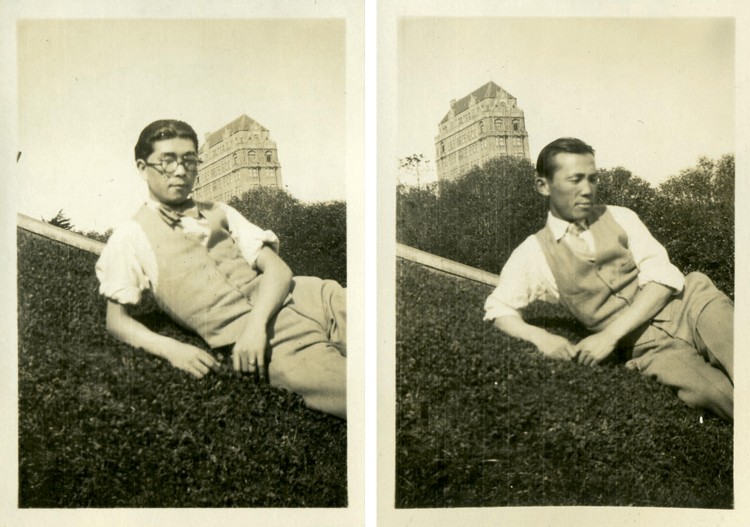

Your latest co-curatorial project, “Seen and Unseen: Queering Japanese American History Before 1945,” is a virtual exhibit that focuses on the history of queer Nikkei (Japanese Americans). What do you hope this project will bring to public perceptions of queer and Asian American history?

There’s no doubt that Asian Americans are largely overlooked in queer history. Asian Americans themselves have largely come to believe that there are no queers in their history before 1965. Nikkei folks in particular tend to attribute homo and transphobia onto their Japanese heritage assuming that their Issei grandparents or predecessors were closed-minded toward queers. I hope that “Seen and Unseen” is able to illuminate a different past, one filled with queer acts and genders even if they didn’t have the language that we have now and an immigrant community that accepted the existence of transgender identities and same-sex desires. I remember when I first began working on this exhibit with co-curator Stan Yogi. He wrote a first draft of the opening text that narrated an Issei oppressive community. I told him about articles in the Japanese language press as well as Andrew Leong’s work who talks about the Issei being “mixed” and “queer,” in its very formation. He later noted that it was the most unexpected thing he learned from doing the project.

Do you have any advice for graduate and undergraduate history students interested in public-facing work? Have you ever found it necessary to shift away from, or perhaps unlearn, any particular academic tendencies in your work as a public historian and curator?

We have a tendency in our profession to wordsmith until our fingers are ground down and use language that normal people do not use. As historians, our field demands that we use more accessible language so we are already one step closer to public projects than folks in other disciplines. Still it’s important to remember that the text on a chat panel is not the same as text in a publication with your name on it as single author. The chat panel will come down after six months and no one even knows who wrote it. So, first tip would be to lighten up about the writing and be sure to avoid jargon.

Second tip is that community partners may not have read Munoz, Butler, or Foucault. It’s important therefore to not assume knowledge that you have acquired through four years of brutally obtuse seminars. With gentle kindness inform community partners of the latest developments in the field.

Often my community partners or the volunteers on my team are retired cisgender white gay dudes. They are for the most post respectful, but every now and again I face someone who is challenging. Always take the high road and be respectful. Be confident in the fact that you have the credential and have an active intellectual life. You may be tempted to reject idiocy and retreat into your ivory tower, but do not let these community curmudgeons derail your engagement with the public.

One of the reasons I became an academic was so that I could be the boss of my own work. In public projects you must let go of control and not be so disheartened if things do not go your way. Obviously you don’t want things to let go of things that are crucial, but there are so many other things that may not be crucial for the project to be completed well.

Last tip, do not look down on being a gun for hire. When the National Parks Service came to me to write “Breathing Fire,” I initially said “no” since it wasn’t MY project. In the end it has been one of my most important publications.

Emily (Emi) Donald is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at Cornell University. Their dissertation project is about the history of queer thought in twentieth-century Thailand, with a particular focus on how the category of tomboy, or thom, travelled and took on various meanings across local and transnational spaces and within popular and activist discourses.