Listening to Migrant Workers and Material Culture

Lyrianne González is a third-year PhD Student in History at Cornell University and the Fall 2021 PHI Graduate Fellow. In today’s story, she reflects on her work this past summer as a fellow in the Smithsonian Latino Museum Studies Program.

Growing up, my parents frequently took my brother and me to the Museum of Latin American Art (MOLAA) and LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes. MOLAA and La Plaza made Latinx art and history accessible. Their programming provided an education my parents knew their children would not receive in school. It was in these moments that my passion for Public History was born and nurtured.

This past summer, I was honored to be a 2021 Smithsonian Latino Museum Studies Program (LMSP) Fellow. This program was the prime opportunity to bring together my Latinx Studies and Public History interests. My research focuses on the racial and generational legacies of the various U.S. guestworker programs. Through oral histories and archival material concerning education, my undergraduate thesis examined the narratives of the children of former Braceros, Mexican guestworkers that came to the U.S. during World War II. As a graduate student, I have expanded my scope to other guestworker groups, including British West Indies guestworkers who worked along the east coast.

Due to my research interests and oral history experience, I was appointed to the “Latinx Agricultural Workers & Workplace Sanctuaries” project hosted by the National Museum of American History (NMAH). As part of this project, I explored the experiences of Latinx migrant workers in meat processing plants through oral histories, archival material, and objects. These stories illuminated the history of Mexican and Central American migration and settlement to the U.S. South. Other topics that emerged include labor employment patterns, religious networks, Latinx civic engagement, and how the COVID-19 pandemic impacted migrant workers’ daily lives.

My first task as part of this project was to participate in a meeting that the project’s curators organized with the community organization that the Smithsonian was in collaboration with, the Episcopal Farm Worker Ministry (EFWM). The goal of the meeting was to discuss collecting oral histories and objects from the agricultural workers the organization serves. For almost 40 years, EFWM has worked with agricultural workers and immigrant families in Eastern rural North Carolina, providing services, leadership programs, community education programs, and advocacy to support the community. As my first introduction to museum practices, this meeting was incredibly enriching. I learned about best practices with stakeholders, maintaining funding as a federal institution, and object acquisition. One of the lead curators mentioned that the Smithsonian is looking for “objects that move people” and the different collecting scales, such as “big objects, wow objects, and medium objects.” I was also confronted by the realities of community-engaged work. Although these are communities, migrant communities are not stagnant, which can complicate continued collaboration.

Following the meeting, I was tasked with creating a guide of interview questions for EFWM to use when collecting the migrant workers’ oral histories. To do this, I examined the transcripts of existing oral histories, noted the questions asked, added related and connecting questions, and thematically organized the questions. I also relied on my previous oral history experience. This included collecting oral histories of the children of former Braceros and of Black farmers in New York, and the questions I asked these two groups. Content-wise, these three groups’ experiences are not identical, but they can share commonalities as minority agricultural workers. As an oral historian, I typically carry out interviews first-hand. However, the act of creating a guide for EFWM further emphasized the vitality of community co-authorship.

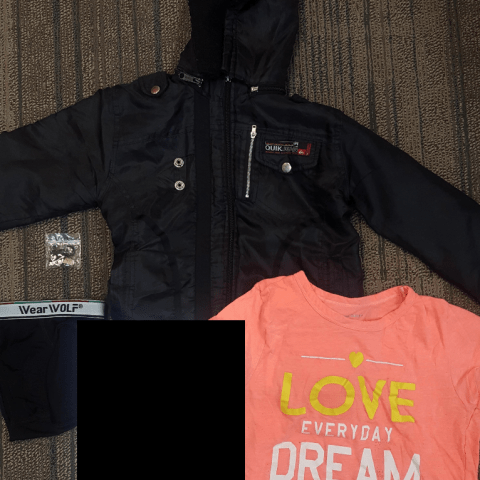

Next, I created object labels for objects collected from the migrant workers. To do this, I referred to existing Smithsonian object labels as examples. I also relied on the oral histories that the objects belonged to; this was essential to understanding and communicating an item’s personal context. I also found it essential to utilize the owner’s words when describing the object. In some cases, I was able to do a reverse image search to get a non-personal historical background of the object. I also translated the labels into Spanish—this was important as the NMAH seeks to expand beyond an English-speaking audience. However, I naturally thought of this as essential, as all objects in museums that I frequent—like LA Plaza de Cultura y Artes and the Museum of Latin American Art—have bilingual object labels. Continuing in the goal of bilingual materials, my last task was to check Spanish to English translations on a digital storytelling website that NMAH created, named the Stories of 2020.

As a 2021 Smithsonian Latino Museum Studies Program Fellow, I gained a multitude of museum work experience that simultaneously enriched my research focus. Reading the various oral histories’ transcripts alongside collected objects and the Stories of 2020 revealed several themes related to my research that will enrich the questions my dissertation asks. These themes include sacrifice, essential migration, exploitation, familial hardship, and the pursuit of better lives for one’s children. Investigating Central American and Mexican workers’ experiences in meat processing plants in the South expanded my research’s geographic and thematic breadth. It is imperative to expand my scope to include the experiences of Central American agricultural workers, who now constitute a large portion of Latinx agricultural workers in the U.S. As part of a national museum team, I directly collaborated with stakeholders. For the first time, I worked with material culture by writing object labels for a public audience. Exploring object material alongside oral histories was unexpectedly extremely heart-wrenching, and that is precisely why institutions like Smithsonian have the responsibility to draw attention to these stories to the public.