Bringing Latinx Labor History to the Public: A Q&A with Mireya Loza

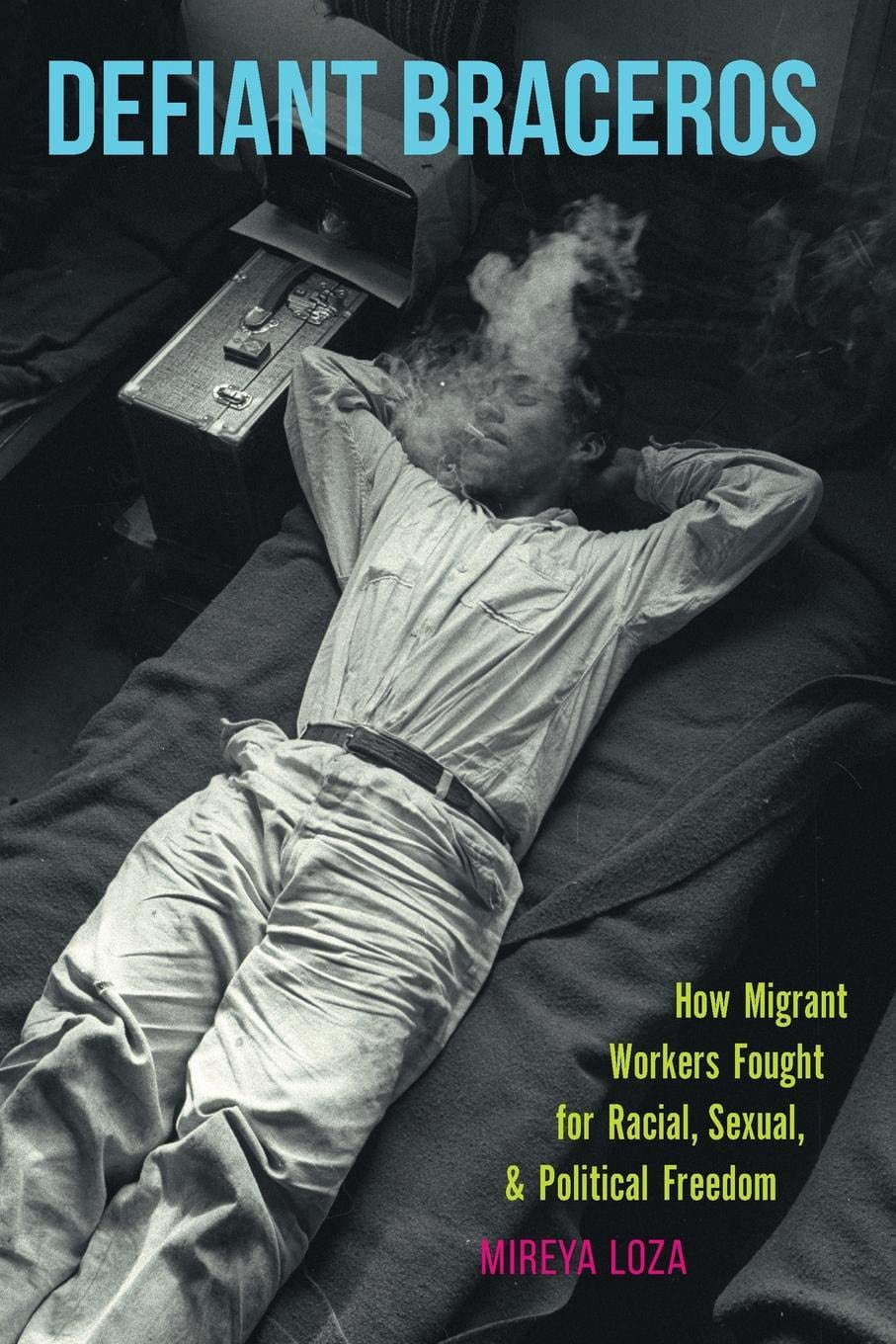

Mireya Loza, Associate Professor in the Department of History and the American Studies Program at Georgetown University, curated and led the National Museum of American History’s exhibit, “Bittersweet Harvest: The Bracero Program 1942-64.” Her book, Defiant Braceros: How Migrant Workers Fought for Racial, Sexual and Political Freedom (UNC Press), examines the Bracero Program and how guest workers negotiated the intricacies of indigeneity, intimacy, and transnational organizing. In advance of her November 4 PHI talk, Cornell history PhD student and PHI Graduate Fellow Lyrianne González conducted this Q&A with Dr. Loza about her duality as an academic and public historian.

1. Your scholarly and curatorial work center on Latinx History and Labor History. Can you talk about how you see the connections between these areas of study?

The history of Latinx peoples is the history of working people and working-class history. Most of my research begins with questions such as: what kind of work people do and what type of working conditions do people labor under, and what are the structures that condition that work? Most importantly, how does their work shape other aspects of their lives?

2. How does food history fit in?

Food fits into my research because many of the people I focus on came to work in agricultural fields across the US. They like to say, “We fed America!” as a reminder that they are the ones that picked the produce that made its way onto our plates.

3. Can you describe what it is like to be involved in two worlds at once? That is the academic world and the public history world as it involves museum curation

Whether it’s creating archives, exhibitions or academic publications, I really enjoy thinking about how we use these avenues to create and share stories about the past. Each has its own limits, challenges and audiences. For example, when I write an exhibition label, I might not be able to say what I can say in an article, but it will probably reach a wider and more diverse audience. It’s an exciting challenge to communicate all my ideas in 50 words.

4. How do you see your role as a public historian? What do you hope your public history work will bring to public perceptions of Latinx History?

I want to contribute to a public conversation that deepens how the nation understands Latinx communities. I want to recognize the labor people contribute to the nation but also shed light on the experiences of these communities that goes beyond solely seeing these communities as a source of labor. I want people to see the messy and complicated aspects of Latinx history and grapple with the reality that there will never be one story that captures all of these complexities.

5. How does being a public historian influence your academic work?

Being a public historian gives me an avenue to reach a broader public than my publications would. People like my immigrant mom or my 17-year-old niece can go see an exhibition or listen to an oral history, and these moments serve as an opening for meaningful conversations about who we are and what we experience. Public History compels me to think about how a broader public learns about the past.

6. What advice do you have for students interested in public history?

My only advice for those who want to participate in public history is to take every opportunity to practice. I remember some of the first exhibitions I curated were very DIY, they featured photographs, photocopied documents and labels. A friend of mine showed me how to use spray adhesive, foam core and an X-Acto knife, so that I could mount my introduction and labels. Nowadays many of my students do a much nicer job using StoryMaps, Instagram, i-Movie, and create websites.

Also, there are a lot of great programs for those interested in Latinx Public History like the Smithsonian’s Latino Studies Program and VOCES Oral History Summer Research Institute at the University of Texas-Austin.

Lyrianne E. González is PhD Student in the Department of History at Cornell University and the Fall 2021 PHI Graduate Fellow. Her research focuses on the racial legacies of U.S. agricultural guestworker programs.