Mobilizing Research with Landscapes of Injustice

by Kaitlin Findlay

Donald and Francoise Jinnouchi offered me tea when they welcomed me into their home in 2016, a year after I found archival records of Donald’s mother, Masue Tagashira. Masue was one of the 21,460 Japanese Canadians who the Canadian government uprooted, interned, dispossessed, and forcibly dispersed in the 1940s. She and her life-partner, Rinkichi Tagashira, had fought their dispossession from the start, when the government seized their property, until its final sale in 1944. In 1948, they testified at a federal commission that investigated the forced sales and pushed the government to be accountable for its wrongdoing. Donald was a teenager in those years and recalled writing the letters of protest for his father, his handwriting the better of the two.

When the Canadian government finally lifted the restrictions on Japanese Canadians’ movement in 1949, Masue and Rinkichi returned to Vancouver, to live only a few blocks away from their former home. They made their living in new ways, but the loss of what they once had lingered. Rinkichi’s tobacco and wholesale shop, the Tagashira Trading Company, had been the achievement of over three decades of investment and sacrifice. After his eventual passing in the 1970s, Masue took his frustration as motivation to join the Redress movement, which in 1988 achieved Canada’s first federal acknowledgement for wrongdoing. The day after the Prime Minister apologized in parliament for the wartime policies, journalists visited Masue in her home and captured her tears of happiness. Donald and Francoise recalled her and Rinkichi’s memory with tenderness and love, remembering them as resilient, steadfast parents. Our conversation in 2016 traversed joyful and painful memories, recalling Masue and Rinkichi’s personalities in a way that escaped the archival records. The conversation informed my MA research, and I was deeply honored when they asked for a bound copy of my thesis for each member of their family.

This research took on a new life in 2018, when it joined Landscapes of Injustice, a community-engaged public history project that partnered universities across Canada with Japanese Canadian organizations and institutions to research and tell the history of the dispossession. After three years of research, the project pivoted to focus on outreach. As a research assistant for Landscapes of Injustice, I had digitized archival records and supported several research publications. Now, hired as the Research Coordinator, I served as an intermediary between the researchers and educators, curators, and writers brought on to communicate the academic analysis to a range of audiences across Canada.

In this position, I became something that is rare for a history student: part of a team. I joined museum exhibit workshops and community consultation sessions alongside curators and designers, presented at teacher resource development sessions with elementary and secondary school instructors, and wrestled with the ethical considerations of an archival database with digital humanities professionals and archivists. I coordinated website development and ended up on personal terms with archivists and copyright offices, to whom I sent seemingly endless permission requests. As I gained skills in public outreach, consultation, and data management, I also learned the specificity and value of my training in history, with insight into research analysis and familiarity with archival holdings.

Now completed, the Landscapes of Injustice project has received provincial and national recognition for its innovative approach to public history, most recently a 2022 Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC) Impact award. This, in part, lies in its union of academia, heritage institutions, and community leaders and professionals. Representatives from leading Japanese Canadian organizations formed the Steering Committee, practicing professionals led the different public history initiatives, and a Community Council oversaw, parallel to the Advisory Committee, the whole project’s work. In addition to this collaborative project design, Japanese Canadians became affiliated with the project through oral history interviews and individual research projects like my own. With students coming and going, the entire project averaged seventy members throughout its seven years.

The pivot to public history had me consider my research in a new way. I had to step back from an argumentative style and think creatively about how to communicate key concepts. When it came to archival material, accessibility and visual “interestingness” took on a new premium. My MA thesis—an analysis of a Royal Commission, illuminated through the story of a family’s struggle to achieve justice—became material for insight into government political and administrative process and one family’s longer history.

In the accompanying museum exhibit, Broken Promises, which first appeared at the Nikkei National Museum and Cultural Centre in Burnaby, British Columbia, my research into hundreds of Commission case files informed a “wall of photographs”—a collage of the bureaucratic and personal photographs, submitted as evidence, of real estate (in the government’s view) and homes (in the eyes of Japanese Canadians.) Presenting dozens of homes, in locations and styles recognizable to many Canadian visitors, the “wall of photographs” communicated the magnitude of the dispossession and the fundamental conflict between the understandings of property and value. A field of academic analysis undergirds this concept, but we offered it in the exhibit for visitors to consider on their own.

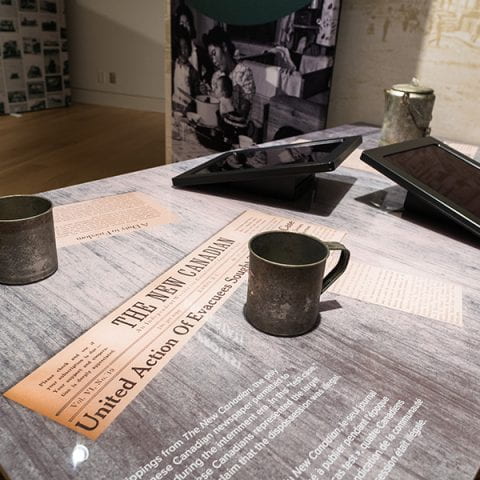

In public history form, an analysis of state power and legal history served as a backdrop to the primary narrative of Japanese Canadian experiences. The stories of seven Japanese Canadian families wove through the museum exhibit, teacher resources, and public history website. We chose families and individuals who could represent the diverse experiences of Japanese Canadians and with whom our team already had relationships. For me, it was an opportunity to continue working with three generations of the Jinnouchi family (who kept Masue’s name from her first marriage), who graciously helped us choose the right photos and loaned belongings for display. To communicate the family’s life prior to the uprooting, we displayed a ledger from the Tagashira Trading Co., a tobacco tin, and an obi sash from one of Masue’s kimonos, all from before 1942.

In relation to Japanese Canadians’ stories, I learned a hard lesson: that often, in public history, less is more. We undertook a careful process to select oral history clips that could communicate the breadth of Japanese Canadians’ experience. The stories were often surprising, moving, and heartbreaking. A woman recalled her mother rowing out into the ocean in the middle of the night to toss a family heirloom, a samurai sword, overboard to keep it from government hands. A man described his fierce anger, as a teenager, at the Canadian state for betraying the values of democracy and justice that he had learned in class. Descendants, closer to my age, explained the significance of the few belongings, seemingly mundane things like a rice tin, that they had from their family’s internment years.

Each voice is important, yet for the museum exhibition we had to select which clips visitors would hear. This process taught me to consider the visitor’s capacity to absorb material. It was also my first real encounter with how the logistics of exhibit fabrication and shipping inform the curation process.

When the Landscapes of Injustice public history initiatives launched in fall 2020, I had the immense pride of seeing Donald Jinnouchi, with his family, visit the exhibit. We had worked with them every step of the way—they had already seen the text, photographs, and objects that featured in their story—but walking through the exhibit prompted more stories and sharing amongst the family. I hope that it can inspire storytelling and discussion of this difficult past amongst the other families who visit. The exhibit is on tour across Canada until fall 2024, alongside a mini-traveler developed to visit smaller regional museums and cultural centers that have direct relationships to this history.

The public history initiatives of Landscapes of Injustice have a mixed target of Japanese Canadian and general audiences. Different people, depending on their experience and history, will relate to the content in different ways. Our community council, and many of the Japanese Canadians we interviewed, held the firm conviction that the internment and dispossession of Japanese Canadians is a history that all Canadians should know, and that this knowledge can build a more just future. The digital archive, with its thousands of case files and over a hundred oral histories, stands as a unique opportunity to continue this aim. There, Japanese Canadians can research their own family’s story, to fill in details and get a better understanding of the past. Already, Japanese Canadian artists have taken this new resource in stride. Filmmaker, writer, and visual artist Linda Ohama, for instance, created a site-specific play inspired by reading the transcripts of her grandfather’s testimony at the Commission. The aim of Landscapes of Injustice was to make this history better-known and, with the educational and archival resources launched, we are excited to see what scholars, creative professionals, and community members pick up from what we’ve done.

Kaitlin Findlay is a graduate student in the Cornell History Department. Her research interests include international law, humanitarianism, forced displacement, and memory in a North American context.