Photographing in the Aftermath: An Interview with Lori Grinker

Lori Grinker is a photographer, transmedia artist, and educator based in New York City and Newburgh, New York. Over the last four decades, she has chronicled the aftermaths of loss and displacement at both a global and personal scale, always with an eye and ear for the ways ordinary people grapple with trauma. Her book Afterwar (2005) drew together fifteen years of photographs of people whose lives were transformed by violent conflict, across continents. She next chronicled the lives of refugees from Iraq, forced to flee following the U.S. invasion. At the same time, she has explored how loss and migration have shaped her own life—including the project Dear Grinkers, tracking down members of her father’s family line from South Africa to the Ukraine, and the transmedia installation Six Days from Forty, about her brother Marc, who died from illnesses related to AIDS in 1996. More recently her photographs from the aftermath of the World Trade Center attack on 9/11 were written about in Smithsonian magazine. PHI director Stephen Vider interviewed her by Zoom, in advance of her talk on November 11.

Lori Grinker is a photographer, transmedia artist, and educator based in New York City and Newburgh, New York. Over the last four decades, she has chronicled the aftermaths of loss and displacement at both a global and personal scale, always with an eye and ear for the ways ordinary people grapple with trauma. Her book Afterwar (2005) drew together fifteen years of photographs of people whose lives were transformed by violent conflict, across continents. She next chronicled the lives of refugees from Iraq, forced to flee following the U.S. invasion. At the same time, she has explored how loss and migration have shaped her own life—including the project Dear Grinkers, tracking down members of her father’s family line from South Africa to the Ukraine, and the transmedia installation Six Days from Forty, about her brother Marc, who died from illnesses related to AIDS in 1996. More recently her photographs from the aftermath of the World Trade Center attack on 9/11 were written about in Smithsonian magazine. PHI director Stephen Vider interviewed her by Zoom, in advance of her talk on November 11.

A lot of your work grapples with loss after it has happened. What do you think it is that draws you to aftermaths?

Let’s start with Afterwar. I was trying to understand how war lives on in people who were on the front lines, and for me that was men, women and children around the world. You know, there was a big question: how do you photograph the war when the war is over? Because it’s never over for these people. I started by trying to do particular stories about people getting back into society, with the help of therapy for PTSD, about healing physical wounds and veterans helping each other. The thing that came out of it for me was the closeness that these people felt sometimes—of course, those who fought together, but also those who fought against each other. It was like they had this shared experience. Talking to people who are from all the different sides of different conflicts, even former enemies—they had so much in common and I felt like they could really represent 20th century war. And then, the invasion of Iraq happened, and we were into 21st century war. All our traumatic experiences stay with us. How do you grapple with them and how do you photograph them in the aftermath? Natural disasters, war—those are the extreme things in life that, where I came from, Long Island, New York, seemed like something I would never go through. And I just needed to understand what that was like.

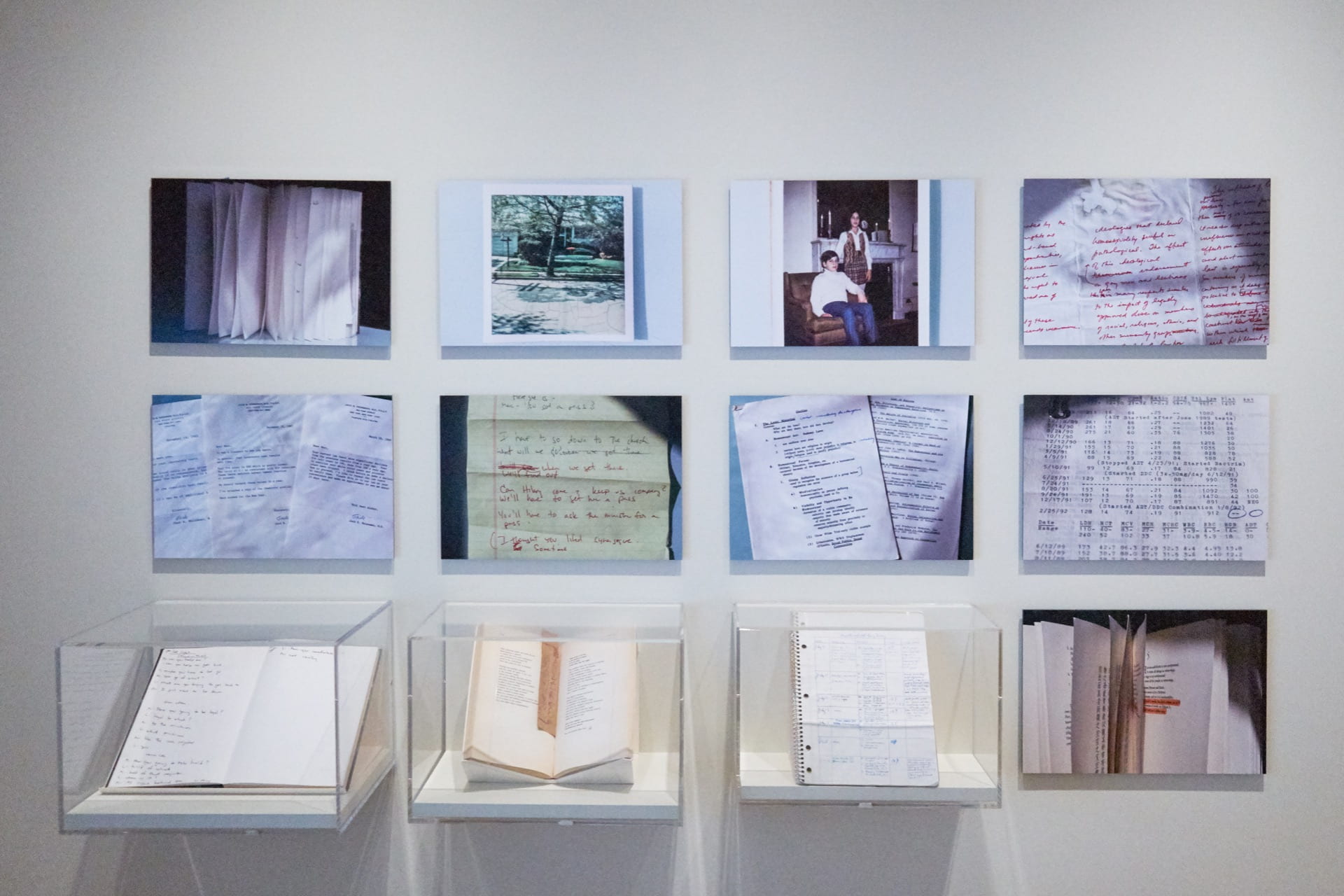

With Six Days from Forty, about my brother: my brother came out as a gay man when he was about thirty years old. Shortly after he was diagnosed with HIV and had to kind of come out all over again because we kept that a secret for quite a while, until he got too sick to keep it secret anymore. My brother was a lawyer, and, in the end, he stopped practicing—he did corporate law—it was too stressful. But he always loved teaching and he got a job at the Illinois Institute of Technology (Kent) Law School. At Kent he started to do some of the work that he really wanted to do; writing with students who formed, as they called it then, a gay and lesbian group. The students were helping him write a book about the history of the lack of laws and rights for gay people and how that led to the AIDS crisis. He never got to finish it, but that became part of Six Days from Forty, trying to tell the story about my brother, with his work and with my work and combining them. I think about my brother every single day—he was a very strong presence in my life so, how do you hold on to that?

The Smithsonian article by Nora McGreevy looks at your photographs of three firefighters raising the American flag at the site of the World Trade Center, and compares your photograph with those of two other photographers taken at the same time. One thing McGreevy points out is that your photograph has a much wider frame and it’s more of a landscape that actually dwarfs the firefighters, whereas the other photographs seem more intentionally patriotic. I wonder if you agree with that interpretation and how conscious you were in that moment of a tension between a kind of critique or skepticism and patriotism.

Thomas Franklin is the one whose picture became the postage stamp and Ricky Flores is the one who was at the same spot as me, but he came in after. Both of them I think were using long lenses—a long telephoto lens will compress the image and bring the subject closer to you and make it seem larger. I was using a wide angle lens and I was really interested in the whole scene; what you could see behind them, you know, the parts of the building that were still there, and in the rubble, when you really look deeply into the photograph you see fire trucks under there that are so dwarfed. They’re both news photographers and I wasn’t. So there’s the whole question about photographing news, not as news. I was used to doing features and not things that had to be published right away—not thinking about a deadline, although I did have a deadline that day.

As far as patriotism goes with the firefighters, they took that flag off a sailboat and I saw them walk around and go back there. I think that they were being patriotic. I think they were also being defiant. The firefighters down there were amazing, and we lost so many of them. I think for them, it probably was patriotism, it was like an instinctual thing, something they had to do in the face of this attack.

You and I first got to know each other through Six Days from Forty, which was included in AIDS at Home, an exhibition I curated at the Museum of the City of New York. One of the things I’m really drawn to in your work, is that you often focus on objects—on people’s belongings as a way of telling their story—not only in Six Days from Forty but also Dear Grinkers. In that project you sought to chronicle the dispersal of your family from Eastern Europe, and while there are many evocative portraits of people, they are also really gripping portraits of things—like flowers, mirrors, paintings—and also these fascinating juxtapositions, like a portrait of Lenin next to a stack of dirty dishes. I’m curious how you think about objects in your work.

Well, it was interesting with Dear Grinkers because I didn’t want to photograph people, and I was also kind of tired of these very intimate projects like Afterwar, which really took an emotional toll on me. You’re giving everything when you’re photographing and taking in people’s stories and it’s such an honor and a privilege to be able to do that. But you take it in, and you hold on to it. I wanted a break from that so I just wanted to photograph landscapes and still lifes that would give a sense of where these people lived and how they lived, and talk about their culture and their personalities, through their objects and through their decor. In the end I did do portraits, even though I was very much against it in the beginning.

And, you know, when my brother was gone, I had nothing else to photograph but some of these things I have from him or from experiences with him—like a coffee mug from Starbucks when it first opened in Chicago in the 80s. We would go there and have breakfast sometimes at this little counter. We’d bring the New York Times, and I bought that mug there. It’s really heavy and I don’t use it as much anymore, but it’s a sacred object, because it represents that really special time with my brother right before he got so sick. All those objects, they’re just embedded with meaning. And of course, it’s the way you photograph it that helps other people connect to it. I always tell my students to photograph objects in people’s homes because it’s integral to their story. But it’s not enough just to take a picture of it as documentation, it really has to be with a creative eye and a lot of feeling.

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Stephen Vider is Assistant Professor of History and Director of the Cornell Public History Initiative at Cornell University. His new book, The Queerness of Home: Gender, Sexuality and the Politics of Domesticity, will be published in December 2021.